rimpl.photo

Emptiness

(and the essence of photography)

Emptiness

(and the essence of photography)

It is now almost two years ago that my dad has passed away and for nearly one year I thought about publishing this photo gallery which is the far most personal of my gallery. But maybe it is not so much about the pictures but more about the thoughts. And at the end it will end up as a long essay with some pictures.

Photography is my passion since my late teenager time. From a philosophic point of view I asked myself often what is the purpose of taking pictures. Photos in our days are like words: countless and only few contain a message or are worth being kept in mind.

But when we go back to the early age of photography, the sense, the meaning of a photo was to materialise a piece of memory: A picture of the family, a portrait of the ones we love, a special scene or landscape worth taking the time and the money to get an immortalisation of what our eyes could see at that unique moment.

Then with time, progress, digitalisation and probably most with the emergence of smartphones the value of an individual picture decreases, sometimes so close to zero that 20 pictures are taken in a series without a single one worth to be kept.

But the intention of some pictures is still to capture an ephemere moment, an emotion, a portrait of our children or our love - to immortalise this instant in time.

Two years ago I rediscovered this essence or sense of photography - unintended and not really in a happy context: keeping an emotional moment alive.

Our dad passed away in the evening two days before Christmas. My brother and me were on his side until his last breath and it was a vey intensive emotional experience. Still today I then think back to the last hours in the hospital.

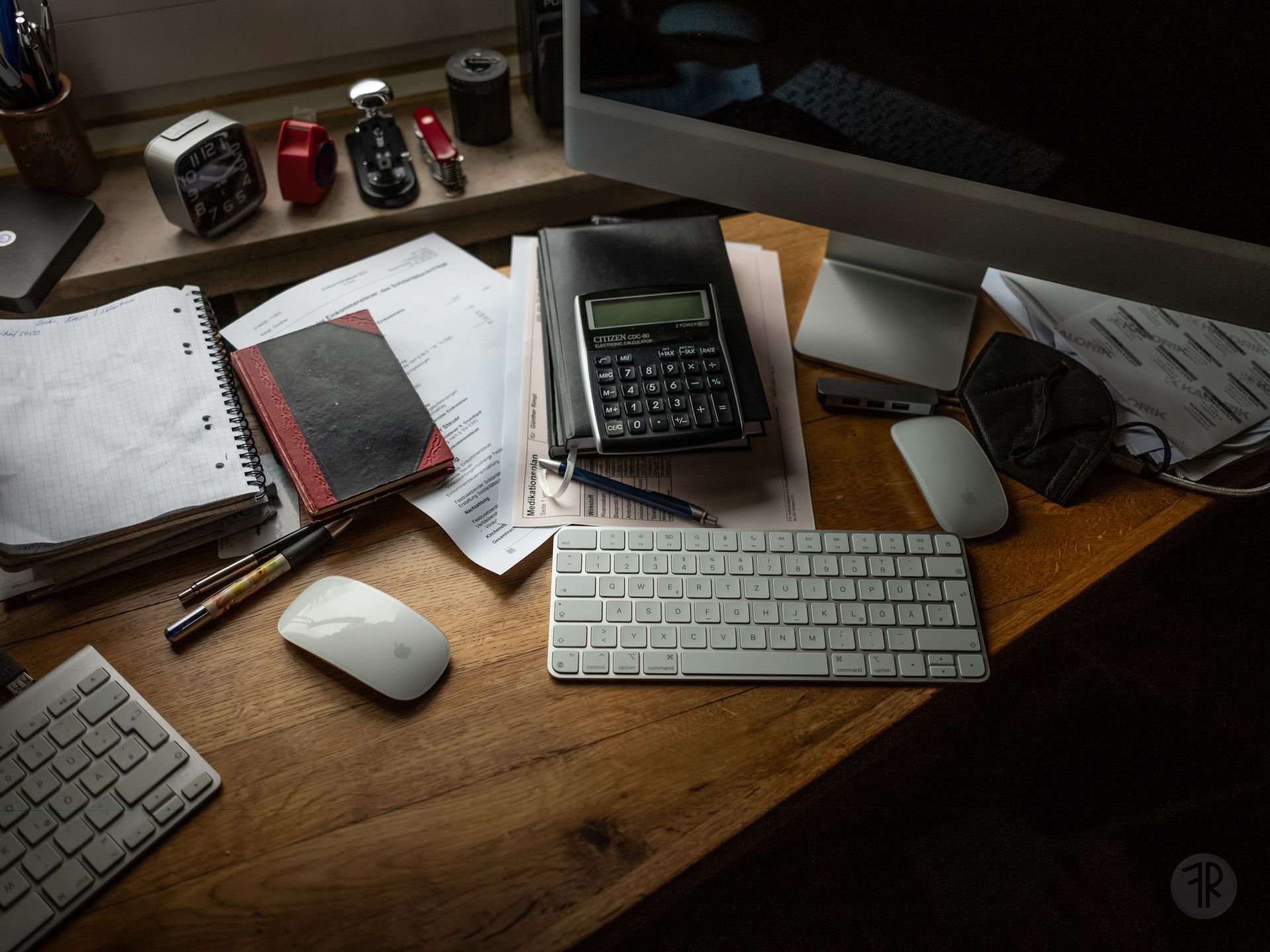

The morning after he has passed away I stayed some hours in his apartment. I wanted to feel his presence in the places where I used to see him the earlier times when I came back to my old home: at his desktop where he spent most of his day, even being retired since seven years; at the kitchen table where he had his breakfast, eating the roll prepared in his small electric table top oven as he could not kneel down to the regular oven anymore, or on the terrace where he used to smoke too many cigarettes each day.

It was a surreal situation. Everything was mainly unchanged from the moment when he left for the hospital two weeks earlier and I could see him when I closed my eyes.

When I returned home before Christmas 2022 I did not meet my dad at home anymore. After the call from my brother that our father is in hospital I left a week earlier than planned for my home trip and visited my dad during his last days in the hospital. The first days gave hope that he might recover but during the last 3 days he had a fall back.

The fact that my brother and me could accompany him until the last breath gave us consolation. Our dad lived rather reclusively but at least during his last hours he was not alone. And the fact that our dad gave us a healthcare proxy was a big help in a difficult and emotional situation: my brother and me could decide together what kind of treatment would have been his choice if he could still express himself. This helped us so much to make difficult decisions in a difficult time.

Then in his flat, after spending some time at the usual places I discovered the places where I usually did not see him:

In the bedroom with the never-used home trainer that should help him to stabilise his knee arthrosis and aches. But during the last years it only has served as support for clothes and belts.

Two baskets of the last laundry that I have removed from the clothesline some days earlier in the basement and the blanket on the bed were silent witnessed of the hope that he would return from hospital, maybe even before Christmas eve.

In the bathroom I found silent witnesses of his daily challenges for personal hygiene: a bathtub seat and a plastic bin probably used for cleaning himself.

I imagined only at that moment how hard it must have been for him achieve these daily tasks that we consider easy and normal as long as we have a good physical mobility. But, with severe knee and hip arthrosis, feet and toes become regions of the body that difficult to reach and a bathtub becomes a high wall to climb above.

It is now almost two years ago that my dad has passed away and for nearly one year I thought about publishing this photo gallery which is the far most personal of my gallery. But maybe it is not so much about the pictures but more about the thoughts. And at the end it will end up as a long essay with some pictures.

Photography is my passion since my late teenager time. From a philosophic point of view I asked myself often what is the purpose of taking pictures. Photos in our days are like words: countless and only few contain a message or are worth being kept in mind.

But when we go back to the early age of photography, the sense, the meaning of a photo was to materialise a piece of memory: A picture of the family, a portrait of the ones we love, a special scene or landscape worth taking the time and the money to get an immortalisation of what our eyes could see at that unique moment.

Then with time, progress, digitalisation and probably most with the emergence of smartphones the value of an individual picture decreases, sometimes so close to zero that 20 pictures are taken in a series without a single one worth to be kept.

But the intention of some pictures is still to capture an ephemere moment, an emotion, a portrait of our children or our love - to immortalise this instant in time.

Two years ago I rediscovered this essence or sense of photography - unintended and not really in a happy context: keeping an emotional moment alive.

Our dad passed away in the evening two days before Christmas. My brother and me were on his side until his last breath and it was a vey intensive emotional experience. Still today I then think back to the last hours in the hospital.

The morning after he has passed away I stayed some hours in his apartment. I wanted to feel his presence in the places where I used to see him the earlier times when I came back to my old home: at his desktop where he spent most of his day, even being retired since seven years; at the kitchen table where he had his breakfast, eating the roll prepared in his small electric table top oven as he could not kneel down to the regular oven anymore, or on the terrace where he used to smoke too many cigarettes each day.

It was a surreal situation. Everything was mainly unchanged from the moment when he left for the hospital two weeks earlier and I could see him when I closed my eyes.

When I returned home before Christmas 2022 I did not meet my dad at home anymore. After the call from my brother that our father is in hospital I left a week earlier than planned for my home trip and visited my dad during his last days in the hospital. The first days gave hope that he might recover but during the last 3 days he had a fall back.

The fact that my brother and me could accompany him until the last breath gave us consolation. Our dad lived rather reclusively but at least during his last hours he was not alone. And the fact that our dad gave us a healthcare proxy was a big help in a difficult and emotional situation: my brother and me could decide together what kind of treatment would have been his choice if he could still express himself. This helped us so much to make difficult decisions in a difficult time.

Then in his flat, after spending some time at the usual places I discovered the places where I usually did not see him:

In the bedroom with the never-used home trainer that should help him to stabilise his knee arthrosis and aches. But during the last years it only has served as support for clothes and belts.

Two baskets of the last laundry that I have removed from the clothesline some days earlier in the basement and the blanket on the bed were silent witnessed of the hope that he would return from hospital, maybe even before Christmas eve.

In the bathroom I found silent witnesses of his daily challenges for personal hygiene: a bathtub seat and a plastic bin probably used for cleaning himself.

I imagined only at that moment how hard it must have been for him achieve these daily tasks that we consider easy and normal as long as we have a good physical mobility. But, with severe knee and hip arthrosis, feet and toes become regions of the body that difficult to reach and a bathtub becomes a high wall to climb above.

Our dad never wanted assistance from care service or household services, even if in his physical situation during his last years would have left no doubt that this was more than a nice-to-have support.

Now, with some distance to the time of his demise, and compared with the ageing of other people in our personal surrounding, my brother and me agree that at least our dad had a self determined life until the end.

And even refusing medical treatment during the last years of his being (which would have helped him for sure to find back a better physical condition and probably would have added some years to his life) was an act of self determination. It is hard to accept this as a relative. But god knows how we will become when we have 6 dozens of years on our life balance.

Back in the kitchen I found a basket with several empty bottles of white wine. They have been in this place at least for months and reminded me that the amount of alcohol he drank each day was more than it should be and probably was a contributor to his medical and social situation.

When I think back to my first memories that I have (in the early 80’s) and when I talk with friends of my generation it seems that alcohol was the collective way for an entire post war generation to try to suppress their trauma and that of their parents. In the young age of my parents drinking was the normality.

The living room has conserved the well arranged mess corner on the rear half of the table. In the years when we still spent the Christmas evening in our dad’s flat he cleaned up this mess just one day before Christmas eve and placed a clean table cloth on the table which remained there for the next 365 days.

But the last years we had our Christmas meal in the first floor at my brother’s and sister in law’s apartment, just above our dad ones. And so the table cloth probably has been there for more than one year.

On the low table at the sofa was the big ashtray made from an engine piston. I has not been used since 2016 when he was in the hospital, the first time for cardiac insufficiency.

The high tech fan helped him to pass heat waves during his last summers, with increasing temperatures each year. Even for me with normal health the temperature peaks in summer become more and more exhausting.

On the small table on the terrace was the ashtray, labelled with his favorite beer brand before he passed to wine. Changing from beer to wine was probably the result of his processing mobility issues: it is was easier to carry 2 bottles of wine than 8 bottles of beer.

The cigaret butts were aligned in order to fill the ashtray as much as possible before emptying it. A surreal scene.

Smoking was, as the medicine told us the day of his passing, the main reason for the hopeless situation: the calcification of the heart valve has caused the heart insufficiency and the smokers lung limited the possibilities of respiratory assistance in the hospital. A fatal combination, which was also the result of his self determination and his unwillingness to accept medical treatment for his main health issues.

It was only during this last visit of his flat that I began to imagine his daily life and how common actions that we consider normal when we a in good health can become daily challenges.

Here and there I found arrangements of objects that have been unchanged since years and many objects were witnesses of his former interests and passions: motorcycle helmets, a self manufactured and never finished gasoline miniature engine. Several home made furnitures of professional quality, tailor made for the purpose or available space. And the Leica M9 on the living room table, with which he has made only some test shots during the last five years, but always kept it ready for use. He even paid attention to charge the battery time and time again.

Our dad gave me the inception for many passions and interests later in my own life: classical BMW motor bikes, photography and collection of cameras, manufacturing of furniture, repair and DIY of any kind, traveling and countless more that don’t come into my mind right now.

But the most important for my own course of life was for sure his relation with Switzerland and more precisely the Valais. We spent countless family holidays in the upper Rhone valley and when I was a young teenager (if I remember well I was 10 or 11 years old) the first long motorbike trip was going to Switzerland, to the Valais. Several other trips should follow until I finally could ride the bike by myself.

This close relation with the Valais was the reason why I finished my studies in Sion, the capital of Valais. And finally I never moved back to Germany. This is now more than 20 years ago.

When he was young he had had the intention to settle to Switzerland. I don’t know what was the reason that he finally didn’t - probably because he met my mother. There are so many things that I don’t know about his early life before he married my mother.

Our dad never wanted assistance from care service or household services, even if in his physical situation during his last years would have left no doubt that this was more than a nice-to-have support.

Now, with some distance to the time of his demise, and compared with the ageing of other people in our personal surrounding, my brother and me agree that at least our dad had a self determined life until the end.

And even refusing medical treatment during the last years of his being (which would have helped him for sure to find back a better physical condition and probably would have added some years to his life) was an act of self determination. It is hard to accept this as a relative. But god knows how we will become when we have 6 dozens of years on our life balance.

Back in the kitchen I found a basket with several empty bottles of white wine. They have been in this place at least for months and reminded me that the amount of alcohol he drank each day was more than it should be and probably was a contributor to his medical and social situation.

When I think back to my first memories that I have (in the early 80’s) and when I talk with friends of my generation it seems that alcohol was the collective way for an entire post war generation to try to suppress their trauma and that of their parents. In the young age of my parents drinking was the normality.

The living room has conserved the well arranged mess corner on the rear half of the table. In the years when we still spent the Christmas evening in our dad’s flat he cleaned up this mess just one day before Christmas eve and placed a clean table cloth on the table which remained there for the next 365 days.

But the last years we had our Christmas meal in the first floor at my brother’s and sister in law’s apartment, just above our dad ones. And so the table cloth probably has been there for more than one year.

On the low table at the sofa was the big ashtray made from an engine piston. I has not been used since 2016 when he was in the hospital, the first time for cardiac insufficiency.

The high tech fan helped him to pass heat waves during his last summers, with increasing temperatures each year. Even for me with normal health the temperature peaks in summer become more and more exhausting.

On the small table on the terrace was the ashtray, labelled with his favorite beer brand before he passed to wine. Changing from beer to wine was probably the result of his processing mobility issues: it is was easier to carry 2 bottles of wine than 8 bottles of beer.

The cigaret butts were aligned in order to fill the ashtray as much as possible before emptying it. A surreal scene.

Smoking was, as the medicine told us the day of his passing, the main reason for the hopeless situation: the calcification of the heart valve has caused the heart insufficiency and the smokers lung limited the possibilities of respiratory assistance in the hospital. A fatal combination, which was also the result of his self determination and his unwillingness to accept medical treatment for his main health issues.

It was only during this last visit of his flat that I began to imagine his daily life and how common actions that we consider normal when we a in good health can become daily challenges.

Here and there I found arrangements of objects that have been unchanged since years and many objects were witnesses of his former interests and passions: motorcycle helmets, a self manufactured and never finished gasoline miniature engine. Several home made furnitures of professional quality, tailor made for the purpose or available space. And the Leica M9 on the living room table, with which he has made only some test shots during the last five years, but always kept it ready for use. He even paid attention to charge the battery time and time again.

Our dad gave me the inception for many passions and interests later in my own life: classical BMW motor bikes, photography and collection of cameras, manufacturing of furniture, repair and DIY of any kind, traveling and countless more that don’t come into my mind right now.

But the most important for my own course of life was for sure his relation with Switzerland and more precisely the Valais. We spent countless family holidays in the upper Rhone valley and when I was a young teenager (if I remember well I was 10 or 11 years old) the first long motorbike trip was going to Switzerland, to the Valais. Several other trips should follow until I finally could ride the bike by myself.

This close relation with the Valais was the reason why I finished my studies in Sion, the capital of Valais. And finally I never moved back to Germany. This is now more than 20 years ago.

When he was young he had had the intention to settle to Switzerland. I don’t know what was the reason that he finally didn’t - probably because he met my mother. There are so many things that I don’t know about his early life before he married my mother.

In all these pictures I feel the emptiness that my dad’s passing away left behind. We met only several times per year but now we will never meet again, we will never talk again and we will never argue again. This is what is called DEFINITIVE.

This journey across my dad’s home and his life showed me how many details of our parents’ life remain unknown to us children.

We usually know much about the time of the life since our parents came together. But their early adult age often hides many interesting details.

Now, passing across the photo albums of our family ancestors gives us a glimpse of their life. But the narrator is missing. No one can tell the story that belongs to the picture.

Maybe this story can be an invitation to those who still have their older relatives: take the time to discover their lives beyond regular family life; try to make them tell you the unknown stories of their lives, the anecdotes. Because once someone is gone things become DEFINITIVE.

Even if I wish that the time I spent with my dad since I left Switzerland would have been more, I don’t write this with tears of regret as I have accepted that, depending on the individual cours of life, we cannot satisfy everybody including ourselves. Time is limited - at daily scale as well as in lifetime scale and if we have an active life it is normal that we don’t have time for all our ambitions.

Life mostly means to leave things undone - unless it is a boring life. We probably cannot spend all the time we would like to with all the people we love - except if we have very limited relations.

I am grateful for the time that I have spent with my dad. We made a lot of holiday trips together even when I was a young adult and we had a good cohesion between him, my brother and me.

I consider myself lucky to have had the occasion to say goodbye to our dad and hold his hand until the last heartbeat. And I am thankful to have taken the occasion freeze my dads imaginative presence in these pictures in order to keep this memory unfaded as long as possible.

When I see this picture I can still see my dad with my inner eyes and I ca feel the emptiness that filled my heart.

Now, nearly two years later, the emptiness nearly filled up with positive thoughts and souvenirs of my dad: the holidays we spent together (mostly driving on our old BMWs to Scandinavia never fearing rain or cold weather; arriving in jeans on the North Cape; making extraordinary friendships that last until today), good moments, things built or repaired together and family events spent with our relatives.

A rich treasure of pictures (mostly taken on film and which I am still scanning in order to have all my pictures digitised one day) makes me rediscover this moments together with him time and times again. And the value of this treasure increases to me the more I rediscover it.

As usually we have the tendency to take pictures of good moments (as we consider these more valuable for immortalisation) the resulting photographic souvenir is mostly a positive one.

All the thoughts, pictures and memories of my dad now fill the former emptiness as scarred tissue is filling the gap after an incision. The loss of a parent is a deep incision and it takes time to cicatrise. And even once the cut isn’t visible anymore the tissue inside is still being transformed for a long time creating one day a final scar that we will carry in our heart and soul until the end of our own days.

In my memories, in many of my activities and in some very personal objects he will continue to exist as long as I exist.

In all these pictures I feel the emptiness that my dad’s passing away left behind. We met only several times per year but now we will never meet again, we will never talk again and we will never argue again. This is what is called DEFINITIVE.

This journey across my dad’s home and his life showed me how many details of our parents’ life remain unknown to us children.

We usually know much about the time of the life since our parents came together. But their early adult age often hides many interesting details.

Now, passing across the photo albums of our family ancestors gives us a glimpse of their life. But the narrator is missing. No one can tell the story that belongs to the picture.

Maybe this story can be an invitation to those who still have their older relatives: take the time to discover their lives beyond regular family life; try to make them tell you the unknown stories of their lives, the anecdotes. Because once someone is gone things become DEFINITIVE.

Even if I wish that the time I spent with my dad since I left Switzerland would have been more, I don’t write this with tears of regret as I have accepted that, depending on the individual cours of life, we cannot satisfy everybody including ourselves. Time is limited - at daily scale as well as in lifetime scale and if we have an active life it is normal that we don’t have time for all our ambitions.

Life mostly means to leave things undone - unless it is a boring life. We probably cannot spend all the time we would like to with all the people we love - except if we have very limited relations.

I am grateful for the time that I have spent with my dad. We made a lot of holiday trips together even when I was a young adult and we had a good cohesion between him, my brother and me.

I consider myself lucky to have had the occasion to say goodbye to our dad and hold his hand until the last heartbeat. And I am thankful to have taken the occasion freeze my dads imaginative presence in these pictures in order to keep this memory unfaded as long as possible.

When I see this picture I can still see my dad with my inner eyes and I ca feel the emptiness that filled my heart.

Now, nearly two years later, the emptiness nearly filled up with positive thoughts and souvenirs of my dad: the holidays we spent together (mostly driving on our old BMWs to Scandinavia never fearing rain or cold weather; arriving in jeans on the North Cape; making extraordinary friendships that last until today), good moments, things built or repaired together and family events spent with our relatives.

A rich treasure of pictures (mostly taken on film and which I am still scanning in order to have all my pictures digitised one day) makes me rediscover this moments together with him time and times again. And the value of this treasure increases to me the more I rediscover it.

As usually we have the tendency to take pictures of good moments (as we consider these more valuable for immortalisation) the resulting photographic souvenir is mostly a positive one.

All the thoughts, pictures and memories of my dad now fill the former emptiness as scarred tissue is filling the gap after an incision. The loss of a parent is a deep incision and it takes time to cicatrise. And even once the cut isn’t visible anymore the tissue inside is still being transformed for a long time creating one day a final scar that we will carry in our heart and soul until the end of our own days.

In my memories, in many of my activities and in some very personal objects he will continue to exist as long as I exist.

switch to gallery:

Emptiness - Rome- Port Laois - London - Scotland - Giant's Causeway - Ireland - Mont Saint Michel -Istanbul

Yalvac and surroundings

-

The bridge -

Roadmen -

Live Concert -

London in 40 hours -

Røros Copperworks